Gio Ponti: Passion for Fornasetti

Collection from the apartment of casa lucano

“My solution for this small home was a reversible play on inlays and visions so that when you look from the living room towards the bedroom, through doors and windows, everything seems to be made in Ferrarese root wood “à la Ponti” (naturalistic fantasy) and when you look the opposite way (from the bedroom towards the living room) everything is covered in Fornasetti’s prints. The colours? A yellow carpet lines the whole floor surface and all the color plays in the printed parts and patterns are juxtaposed against this ‘pedal note’.” - Gio Ponti, Domus (1951)

Among the most prolific talents to grace twentieth century design, Giovanni “Gio” Ponti (1891-1979), a polymath and master of architecture - as well as a designer, painter and journalist - was a true renaissance man. Prolific, eclectic and indefatigable, he designed everything from cutlery to skyscrapers, to the La Cornuta (which translates as “cuckold”), an aerodynamic espresso maker for La Pavoni (1948). Graduating with a degree in architecture from the Politecnico di Milano in 1921, Ponti began his career working as an architect alongside Mino Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia. Originally inspired by the neoclassical Novecento Italiano movement, from L’Ange Volant (1926), the post-Palladian villa he built for Tony Bouilhet, head of the fine silver firm Christofle, Ponti went on to design the revolutionary Pirelli Skyscraper in Milan (1958) and the Denver Art Museum in Colorado (1974). Aside from his completed architectural works, a restless inventor, Ponti worked for over 120 companies. So capacious was his studio, a former garage, that his employees literally rode up to their desks on scooters.

With a love of innovation, quality and craftmanship, Ponti took a new approach to furniture design. Inspired by the traditional and very simple vernacular chairs produced in the Ligurian town of Chiavari, Ponti set out to create a form pared back to the absolute minimum. From his initial drawings in 1941, the chair went through several variations, its first iteration for Cassina, the Legerra (1951), was subject to a further process of distillation, producing the 699 Superleggera (1957), literally, “super-lightweight”. As Ponti said, “the more minimal the shape, the more expressive it becomes.” Weighing less than four pounds, the Superleggera was so ethereal it could be held aloft with just one finger. Minimalist yet incredibly functional, Ponti threw a prototype of the Superleggera from a four-storey building, satisfied when it landed intact. As an advocate for modernity, Ponti sought to make high-quality design accessible to everyone, not just the elite. The first Italian architect to engage the public by writing articles in newspapers (not to mention launching and editing the legendary design magazine Domus.), Ponti’s sumptuous private commissions were paralleled by his low-cost line for Italian department store La Rinascente, thereby making the decorative arts accessible to the greatest number.

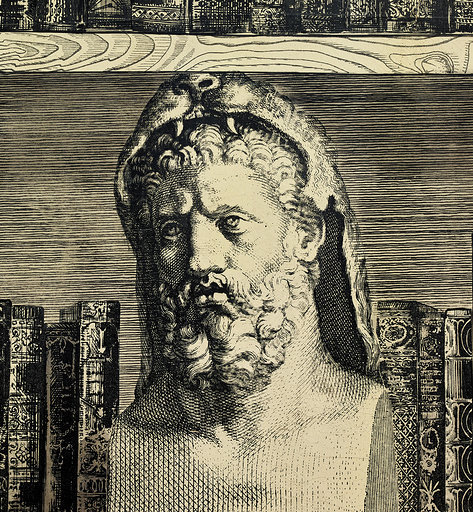

Gio Ponti, Piero Fornasetti, Edina Altara and Guido Gambone, dressing room (c. 1951) in burr walnut-veneer. The side chair, in lacquered wood, transfer printed with Fornasetti’s lithographies, was used as a model for Ponti’s iconic Superleggera 699 chair Photograph: ©Phillips

Gio Ponti, Piero Fornasetti, Edina Altara and Guido Gambone, study and dressing room (c. 1951) in burr walnut-veneer, lithographic transfer-printed wood, painted wood and reverse-painted mirrored glass Photograph: ©Phillips

Reflecting on his career Ponti wrote, “If it were worthwhile to chronicle my life as an architect a chapter (beginning in 1950) could be: ‘Passion for Fornasetti.’ What does Fornasetti give me? With his prodigious printing process . . . an effect of lightness and evocative magic.” (Laura Licitra Ponti, Giò Ponti: The Complete Work, 1923-1978, Boston, 1990, p. 274). Ponti and Milanse designer Piero Fornasetti (1913-1988) first worked together in 1933, forming a relationship that would last decades. Their collaboration intensified in the 1950s when Ponti brought Fornasetti to work with him on numerous prestigious projects which proceeded according to a well-established pattern: Ponti designed and Fornasetti decorated. Together the duo completed many notable interiors including those for the casino of San Remo, the Vembi Borroughs offices, the ocean liners Oceania, Conte Grande and Giulio Cesare, as well as private commissions for the Italian bourgeoisie. Casa Lucano (1951), a large apartment in the elegant Fiera district in North West of Milan, was their first complete interior. To Ponti, Fornasetti’s work was the ideal instrument to achieve a systematic dematerialization of volumes and, at Casa Lucano, the creation of a theatrical Casa di fantasia (fantasy house), as he called it in Domus.

Echoing both the Italian Metaphysical and French Surrealist art of the early and mid-twentieth century, Casa Lucano is a perfect example of the symbiosis of these two prolific talents during the full flowering of their collaborations in the early 1950s. With almost no equivalent in pre-war Europe (except perhaps Le Corbusier’s Beisttegui apartment (1929-31) and Carlo Mollino’s Devalle apartment (1939-40)), Edina Altara, Fausto Melotti and Giordano Chiesa (to name a few), collaborated under Ponti’s artistic direction to create an extraordinary metaphysical interior, Commedia dell’Arte within the domestic realm, where surfaces and volumes merge and dissolve into each other through a succession of carefully designed stage sets. “There are two fundamental aspects to consider in the understanding of this work by Ponti,” says Salvatore Licitra, Ponti’s grandson and creator and curator of the Ponti Archive. “The use of space as an expression of theatrical versatility and the use of surfaces as an expression of 'illusiveness,’ considered by Ponti as an indispensable approach to architecture. In the plan for the Lucano apartment we already find the fundamentals of what will be the programmatic approach of Ponti’s own apartment at Via Dezza, designed in 1957: that is, a unique and versatile space with a succession of infilate ottiche (lines of vision) revealed through the various rooms. It is a sort of stage presenting the lives of its ‘inhabitants’, who animate it and complete its various functions. This reversal, that assigns inhabitants the role to determine the functional destiny of the spaces, is a central theme of Ponti’s post-war work.”

Ben Weaver

Glazed ceramic tile from Casa Lucano, executed by Giordano Chiesa Photograph: ©Phillips

Detail of lithographic transfer-printed wood by Piero Fornasetti Photograph: ©Phillips