In the Midst of Marvel

Marc du Plantier

“Man must live in the midst of a certain marvel” - Marc du Plantier

Somewhere between Jean-Michel Frank and Jean Royère, there is Marc du Plantier (1901-1975); an emblematic figure of the 1940s, during his lifetime he was celebrated as one of the most gifted and brilliant decorators of his day. Eclectic and independent, he worked for fashion houses, designed private residences as well as stage sets and costumes for La Comedie Francaise. Du Plantier’s early work, in the 1930s and 40s has been described as “neo-classicist avant-garde modernist”, but from the post-war years, until his death, his style evolved into something altogether more abstract, inspired by the optimism and exuberance of mid-century design. Rediscovered in the 1980s by gallerist Yves Gastou, as a previously unrecognized talent, to this day, Du Plantier continues to prove perennially popular with collectors. The mystery surrounding his work can be compared to the life and work of Jean-Michel Frank, another purist who was known for a spartan aesthetic of understated luxury, favouring austere, simple shapes in a variety of unexpected materials, such as straw marquetry, parchment and terracotta. Whereas Frank was fascinated by austerity of form, or “poverty for millionaires, ruinous simplicity” as Coco Chanel described his interior designs, Du Plantier was far less radical, and his interiors were truly sumptuous. In addition, Frank collaborated with renowned artists such as Alberto Giacometti and Christian Bérard (both of which influenced his style) and had a gallery on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honore. Du Plantier worked alone because he wanted to be entirely free. He had no agency, no shop, no advisers and he recruited his clientele alone, from the highest social and cultural spheres; completing full interiors for Henry de Rothschild, Juan March and Ali Khan, amongst others. If a taste for minimalism in decor can bring these two creators together, what for Frank was the creed of a lifetime, lasted only a moment for du Plantier, who was later seduced by the mixes of styles and changes in taste. Although praised for his austere neoclassicism, unlike Frank, he was actually much more personal and extravagant in his use of materials, and driven by the fashions and inclinations of the moment.

The round entrance hall of Marc du Plantier’s apartment in boulevard Suchet, Paris, 1936

A parchment covered desk in Marc du Plantier’s study, boulevard Suchet, Paris, 1936

Du Plantier was born in 1901 in Madagascar. Deciding to specialize initially in mathematics, he entered the Ecole polytechnique, but then, changing his mind, he turned to architecture, joining the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in 1922. There he followed the teaching of the classical French architect Gabriel Héraud (1866-1941) and, at the same time, the lessons of the painter Paul Albert Laurens (1870-1934) at the Académie Julian. DuPlantier began his professional career in the fashion industry, delivering models for the fashion houses Jenny, Doucet and Doeuillet. In 1929 he dedicated himself entirely to the profession of interior designer, and already, by 1930, he was known for working only with the Parisian elite and the nobility; with clients included the Princess Jean-Louis de Faucigny-Lucinge, Baron de Fouquières and the Marquis and Marchioness of Casa Valdès. Supported by Christian Bérard (1902-1949) and the art auctioneer, art historian and novelist Maurice Rheims (1910-2003), Du Plantier was quickly entrusted with the design of a number of significant projects, establishing an architectural vocabulary which was characterized by the rigor lines, use of colour, skilful lighting and the play of mirrors.

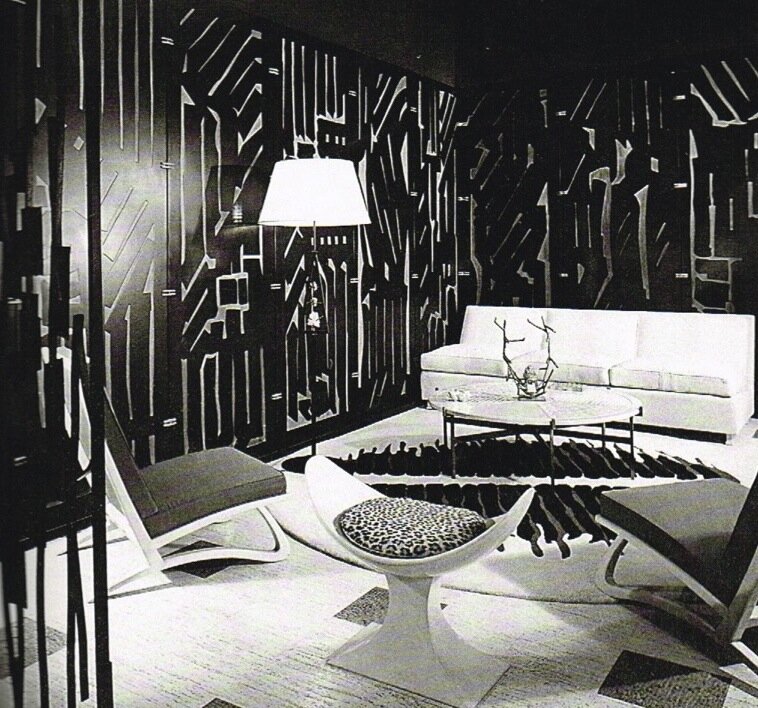

Marc du Plantier’s Los Angeles Gallery, Artedécor in La Cienega Boulevard, 1964

Du Plantier’s early works reveal his taste for the elegant and refined combination of materials, as well as his predilection for the use of golden bronzes appealing to the great French furniture tradition as well as to an idealized classical tradition. Inspired by the simplicity of antique pieces, Du Plantier created timeless furniture, lighting and objects, that managed to bridge perfectly the arts of the past — with a particular penchant for neoclassicism — and the contemporary art of the period. Du Plantier’s designs remain, to this day, immediately recognizable for their unique combination of pared down geometrical forms, with luxurious and rare materials, subtly decadent in ornament, such as semi-precious stones or coral. The highly publicized inauguration of Du Plantier’s personal apartment, on boulevard Suchet in Paris, entirely decorated by him — notably with mirrors engraved by his friend, the French artist Max Ingrand (1908-1969) — was irrefutable proof of the dazzling success of his creations.

It was quickly followed by various orders from the de Rothschild family and soon after, following the installation of Les Du Plantier in a private mansion in Boulogne-Billancourt, the Paris elite would flock to his home, which was the setting for sumptuous receptions, while also serving as a studio-workshop. An exemplary showcase of the refinement of its occupant, the Hôtel is testament to a continued evolution in style towards a pared-back luxurious neoclassicism, carried by superb and rare materials. The focal point, where the designers many friends and acquaintances were invited to dine, centred on a massive white marble table, the room decorated with paintings of Du Plantier’s own design. His proximity to the most prestigious families and artists of his time, such as the French fashion designer Paul Poiret (1879-1944), and Mme Puissant-Van Cleef, enabled him to decorate a secession of sumptuous apartments, as well as the main hall of the new French Embassy in Ottawa, Canada, and furniture for the Elysée Palace.

Marc du Plantier’s bedroom, rue de Belvédère, Paris, 1935

Du Plantier was approached in 1939 to decorate the residence of the Count and Countess of Elda in Madrid; upon the outbreak of the Second World War he was effectively forced to remain there, in “exile”, for more than nine years. His Parisian contacts opened the doors of the capital’s mansions, and, during this “Spanish Period”, his neoclassical pieces were a huge success, both on the peninsula, and elsewhere, exporting what would be called his “wise modernism” to Mexico, Lebanon and the United States. As well as his work at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Du Plantier’s decoration of a luxurious apartment overlooking the Bay of Algiers was considered to be one of the highlights of its time. Upon his return to France in 1949, Du Plantier radically reinvented himself. Erasing from his work any reminiscence of past styles, he favoured the mixing of wrought iron elements, glass and various and varied stones, moving towards an ever-increasing purification and modernism. Eschewing such overt classical references as can be seen in his Egyptian claw-footed oak armchairs of the 1930’s, as he entered the new decade, Du Plantier would design armchairs and tables in gilded and green-patinated steel.

At the beginning of the 1960s, when private orders dried up, Du Plantier settled in Mexico City, where he founded the company Artedécor, then in Los Angeles, before returning to Paris by way of the Orient. From this contact with American pop culture was born the work he developed in 1968, creating models with new materials edited by Galerie Jacques Lacloche and for the dining room of Maurice Rheims, without ever departing from his classic rigor. Back in France, definitively, Du Plantier continued to design furniture until his death in 1975, flourishing in the freedom and modernity of the second half of the twentieth century. “Man must live in the midst of a certain marvel,” said the decorator, a maxim that he himself adopted throughout his life.