The House That Ludwig Built

A DWELLING FOR THE GODS

“You probably imagine that philosophy is complicated enough, but let me tell you, this is nothing compared to the hardship of being a good architect. Back when I was building the house for my sister in Vienna I was so exhausted at the end of the day that the only thing I was still able to do was to go every evening to the cinema. ” – Ludwig Wittgenstein

The Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) grew up in a grand house on the Alleegasse (now Argentinierstrasse) in Vienna, aptly known as Palais Wittgenstein. It would be hard to overestimate the cultural sophistication of the Wittgenstein’s household, which provided an exceptionally intense environment for artistic and intellectual achievement. Wittgenstein’s father, Karl, a wealthy industrialist, was a significant patron of the arts; he owned paintings by Giovanni Segantini, sculptures by Rodin and Max Klinger’s bust of Beethoven. Among other things, he financed the construction of the Vienna Secession building (1898), its interior decorated by Gustav Klimt, who would later paint Karl’s daughter Margarethe. As might be expected, Wittgenstein’s outlook on life was profoundly influenced by the Viennese culture in which he was raised.

Although he shared his family’s veneration of the arts, Wittgenstein’s deepest interest as a boy was in engineering. In 1908 he went to England to study the then-nascent subject of aeronautics. While working on a project to design a jet properer, Wittgenstein developed an obsessive interest in the philosophy of logic and mathematics. Having studied the ground-breaking works of philosopher Gottlob Frege, he visited Frege in Jena who advised him to study with Bertrand Russell. Wittgenstein turned up, unannounced, at Russel’s rooms in Trinity College, Cambridge in October 1911. Within a year Russell declared that he had nothing left to teach him. Seemingly, Wittgenstein agreed, as he left Cambridge to work in remote isolation in a hut he built at the end of the Sognefjord in Norway.

In November 1925, the then married Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein, commissioned a young architect, Paul Engelmann, to design a large modern townhouse on Kundmangasse. At that stage Wittgenstein was a self-imposed exile from his native Vienna. Having almost renounced philosophy, he believed (wrongly) that he had solved all its problems with his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921). Margarethe invited her brother to collaborate with Engelmann, at least in part as a distraction from the scandal surrounding the Haidbauer incident: in 1926 while working as a primary-school teacher, Wittgenstein had hit a boy so hard he passed out. Wittgenstein showed a great enthusiasm for the project and in Englemann’s plans; not only had Engelmann studied under modernist architect Adolf Loos (supposedly his favorite pupil), whose stark modernism Wittgenstein admired, but the two men had become close friends during the war.

Although initial designs were by Engelmann, Wittgenstein gradually took over and completed the project with the same obsessiveness displayed in his academic life. He took to calling himself an architect, even going so far as to change his letterhead to “Paul Engelmann & Ludwig Wittgenstein Architects”. True to the principles of Adolf Loos, Wittgenstein abhorred embellishment. In his 1908 manifesto Ornament and Crime, Loos advocates a clean simplicity; “ornament” is deemed superfluous, having a tendency of “going too soon out of style” and thus becoming obsolete. The effort wasted in designing and creating superfluous ornament Loos saw as nothing short of a “crime”. Wittgenstein embodied these principles, in the way that he dressed, and in his surroundings; and as far back as 1912, his rooms at Cambridge had been furnished with simple custom-made pieces. The Wittgenstein house, begun in 1926, is as manically obsessive as Wittgenstein's moral extremism. Stark and stripped back to its bare bones, it eschews all forms of decoration.

Adding only small elements to the exterior configuration, Wittgenstein accepted the general framework of the house as proposed by Engelmann. However, so as to resolve a conflict between the overall asymmetry of the house, and his desire for a sense of internal symmetry, Wittgenstein greatly refined the layout; in the end resorting to several compromises, for example, structurally unnecessary columns and the thickening of walls. While the central hall is the focus of house, it is not the only center. Instead, the plans suggest multiple centers that further the oscillation from symmetry to asymmetry, both formally and conceptually. The exercise was intellectually absorbing and exhausting for Wittgenstein. It is well documented that he spent a year designing each of the radiators (which, unusually, fold around the corners) as they had to be exactly positioned to maintain the symmetry of the rooms. One of the architects, Jacques Groag, wrote in a letter, “I come home very depressed with a headache after a day of the worst quarrels, disputes, vexations, and this happens often. Mostly between me and Wittgenstein” (Waugh, A. (2008) The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War Random House of Canada).

Stonborough-Wittgenstein House, internal staircase

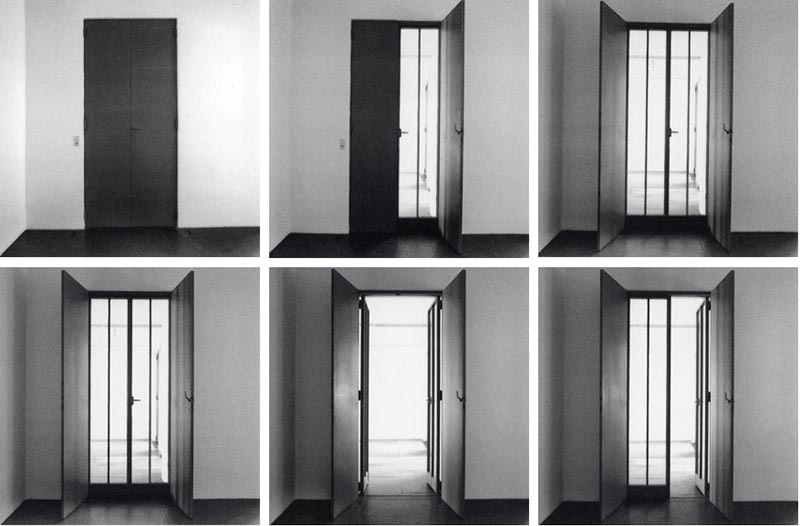

Settling on an internal layout, Wittgenstein turned his attention to what he considered to be the key architectural details, designing everything from windows, doors, handles, paving and even the mechanical plumbing and electrical system. Without such fripperies as skirtings and cornices, walls in stucco lustre run cleanly from floor to the ceiling. Carpets were seen as haphazard, whereas the reflection of the highly polished stone floor creates the sensation that it “dematerializes”. The double doors between each room are particularly striking, highly engineered in steel and glass, their handles are minimalist works of art; simple bent brass tubes, with no covers or faceplates, are fitted directly into the doors, just as keyholes are cut into the frame. In the absence of any decoration they become the guiding element of the interior.

Wittgenstein forbade the use of curtains, which he hated, and so instead, each of the ground floor windows is shaded by metal “curtains” (each weighing approximately 150kg) that can be lowered into the floor. Bernhard Leitner, author of The Architecture of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1973), hailed this “aesthetic of weightlessness”. So that they could be moved easily, Wittgenstein developed an invisible pulley system, as ingenious as it was expensive. Each “curtain” is raised by precisely calculated counterweight; “With the up and down movement of the opaque curtains, one gets a haptic feeling of light” (Zou, H. (2005) The Crystal Order that is Most Concrete: The Wittgenstein House)

Stonborough-Wittgenstein House, door handles that took a year to design

With every surface exposed and every joint foregrounded, there was no margin for error in construction. Despite his lack of formal architectural training, Wittgenstein’s standards were rigorously exacting. “Tell me,” asked a locksmith, “does a millimetre here or there really matter to you?” “Yes!” Wittgenstein roared before the man had finished his sentence. At the last minute, so as to maintain the original proportions of the house (3:1, 3:2, 2:1), Wittgenstein insisted on having the living room ceiling taken out and raised by 30 millimeters.

Though austere, even when compared to the architecture of the contemporaneous Bauhaus, the spaces are as large and as perfectly proportioned as one might expect from a philosopher-architect. Colin St John Wilson (architect of the new British Library at St Pancras) praises the Wittgenstein House for having “none of that blatant self-satisfaction of minimalism”. Describing the work, Ludwig’s eldest sister, Hermine, wrote: “Even though I admired the house very much, I always knew that I neither wanted to, nor could, live in it myself. It seemed indeed to be much more a dwelling for the gods than for a small mortal like me, and at first I even had to overcome a faint inner opposition to this 'house embodied logic' as I called it, to this perfection and monumentality.” Perhaps that might explain Margarethe’s somewhat incongruous decision to fill the house with Biedermeier furniture.

Ben Weaver

Stonborough-Wittgenstein House, facade

Stonborough-Wittgenstein House, radiator