Future Classics

Contemporary collectibles

“I’m interested in the idea of heirloom furniture, that will be passed down from generation to generation, which is, inherently, the antithesis of the sort of fast design pushed by the mainstream media. Quality of craftsmanship was at the core of the process and as such, sympatico with makers was essential. Each piece is unique and bears the mark of the artisan that made it — something I find utterly inspiring, and to an extent, humbling. I like the notion that everything good takes time. Time is essential to create beauty.” — Léo Sentou

Since gallerists such as Félix Marcilhac (1941-2020), Jacques Lacoste (b. 1963) and Anne-Sophie Duval first rediscovered and championed twentieth-century design in the 1970s and ‘80s the market for decorative arts has since exploded, with auction houses such as Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips frequently reporting record prices for works by the likes of Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999), Jean Prouvé (1901-1984) and Gio Ponti (1891-1971). Particular highlights from 2023 include a pair of monumental black lacquer screens (c. 1922-1925) from the apartment of Irish architect Eileen Gray, Francois-Xavier Lalanne’s (1927-2008) cast iron “Babouin-Cheminée” (1984-1985) and a gilt-bronze chandelier (1946-1947; cast c. 1947-49) created by Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) for art collector and patron Peter Watson (1908-56), that sold in February at Christie’s for £2.9m. The somewhat surreal electrolier, with its multilayered armature and sharply pointed branches, had originally graced the offices of “Horizon”, on Bedford Square in Bloomsbury, the cultural magazine Watson co-founded and bankrolled from inception in 1939. Going out of its way to source material from émigré writers, Horizon was one of the most cosmopolitan publications of the mid-twentieth-century, and throughout the war, as literary historian Ann-Marie Einhaus (b. 1981) wryly puts it, remained “a magazine with a European outlook, albeit one shaped by the narrow views of Europe as the inheritor of Greco-Roman antiquity promoted by the English public school system”. Its pages contained essays by eminent art critics, and reproductions of works Watson particularly admired, including those of Giacometti, Francis Bacon (1909-1992), Lucian Freud (1922-2011) and John Craxton (1922-2009). Giacometti’s monumental chef d’oeuvre remained Horizon’s crowning glory until 1949 when the magazine ceased publication and rather curiously it disappeared into thin air. British art critic William Feaver (b. 1943), in his biography of Freud, suggests Craxton — who would have seen the chandelier in Horizon’s offices in the late 1940s’ — made off with it illicitly, but the official story is that he came across it gathering dust in an antique shop on the Marylebone Road in the late 1960s, and recognising its provenance, snapped it up for a modest £250. After that, it hung the music room of Craxton’s mock Jacobean Hampstead home, where it was subjected to an otherwise uninspiring mise-en-scène of fiddle leaf figs, steel stacking chairs and a Victorian wall-mounted china cabinet. Other interesting works from recent sales include Table-bibliothèque “MB 960” (c. 1930) by Pierre Chareau (1883-1950), which sold for €554,000 at Christie’s Paris in November 2023, and Giacometti’s “Coupe Ovale” (c. 1935), executed at an important moment in the artist’s career, as he was moving towards the end of his surrealist phase, that went for a staggering US $1,016,000 at Sotheby’s Important Design sale in New York (see my article “The Common Spirit of the Giacometti Brothers and Les Lalanne”, Sotheby’s, 2023). Giacometti, as French art historian Jean Leymarie (1919-2006) has written, discerned “no rift between the fine and decorative arts”, and as such, like Les Lalanne, Line Vautrin and Christian Bérard (1902-1949), his work served to blur boundaries between fine and decorative arts, ergo leading to a wholesale rethink of the way in which we view the classical canon and in turn, creating a “blue-chip” decorative arts market for works by twentieth-century greats.

The “Low Sideboard”, designed by Garnier et Linker for Galerie Dutko, inspired by the work of French Art Deco ensemblier Eugène Printz, image c/o Garnier et Linker

Léo Sentou was recently appointed to “Le French Design 100” for his wrought iron and alabaster “Side Table L.A”, an elegant, pared-back reinterpretation of a “servante monopole” by master cabinetmaker Louis Aubry

Of course, collectors very often rely on the skills of interior decorators, who in turn spark trends, the result of which has an inexorable effect on the desirability, or otherwise, of certain works. Outside the realm of twentieth-century design, the 1980s saw a demand for eighteenth-century French furniture, in large part, as a result of American designers such as Billy Baldwin (1903-1983) and Mario Buatta (1935-2018), who peppered their interiors with elegant Louis chairs and gilt-gold overmantels. This can be seen to great effect in the sitting room Baldwin created for collector and show-biz lawyer Lee Eastman (1910-1981), which had originally been a typical white-walled gallery-like space, lacklustre and seldom used as a result of its spartan aesthetic until Baldwin clad all four walls in glossy Coca-Cola brown vinyl; a somewhat bold, unexpected gesture, which not only offset Eastman’s extraordinary collection of modern masterworks by Rothko (1903-1970), de Kooning (1904-1997) and Klein (1928-1962) but also served to create a warm, inviting space that became one of the most iconic rooms of the twentieth century. Following on from French fashion designer Jacques Doucet (1853-1929) in the nineteen twenties, eccentric French couturier Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008), famously assembled an unprecedented collection of art and design. His rue de Babylone duplex has since become somewhat mythic, having had an immeasurable impact, not only in terms of its decoration, and the widespread transition toward eclectically appointed interiors, but also on the popularity of Art Deco design. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Jacques Grange (b. 1944) was not only the couturier’s go-to decorator but also the de facto gatekeeper to the clique of models, artists and muses surrounding him; this has, in turn, cemented Grange in the annals of twentieth-century French history to the extent that nearly all contemporary designers immediately cite his extensive opus as a leading source of inspiration. This can be seen clearly in the work of numerous young designers, who, in homage to Grange’s immediately identifiable “paw”, as the French put it, employ “signature” elements such as dentil coving, quilted silk curtains and sofas in “le style Frank”, in the hope of achieving a similarly pared-back, elegant aesthetic. Key to achieving Grange’s particular take on “le grand goût français”, or rather, interiors that inherently evoke an aura of cultured sophistication, are works by the greats of modernism; and, now such is the demand for Eugène Printz’s (1889-1948) “Eventail” tables, Jean Dunand’s (1877-1942) graphic dinanderie vases and Marc du Plantier’s (1901-1975) “Égyptienne” chairs that all but the 0.001% have been priced out of the market. There are, of course, plenty of unsigned works, or even those by second-tier ébénistes, that are suitable for creating “the look”, as it were, but, that still leaves something of a vacuum. As such, it’s an opportune time for contemporary artists and makers to produce works that will inevitably, one day, become collectables of the future. This might come far sooner than one might first imagine, for example, at PAD London last year Galerie Jousse Entreprise showed works by French industrial designer Philippe Starck (b. 1949), including an “Illusion” table in bronze and moulded glass and a pair of aluminium “Tito Lucifer” andirons, all produced in the latter half of the twentieth century; indeed “collectible design”, seemingly, is a term expanding to encompass an increasingly contemporary coterie of ensembliers.

New York-based decorator and designer Brett Robinson’s cast aluminium stool, upholstered in plush alpaca, its undulating lines reminiscent of Mark Newson’s “Orgone” collection, image c/o RG Brett

Ian Felton’s “Sacha” coffee table, named after the Quechua word for “Tree”, with its root like, rough-hewn oak base and glazed lava stone top, evocative of submerged Cora, image c/o Ian Felton

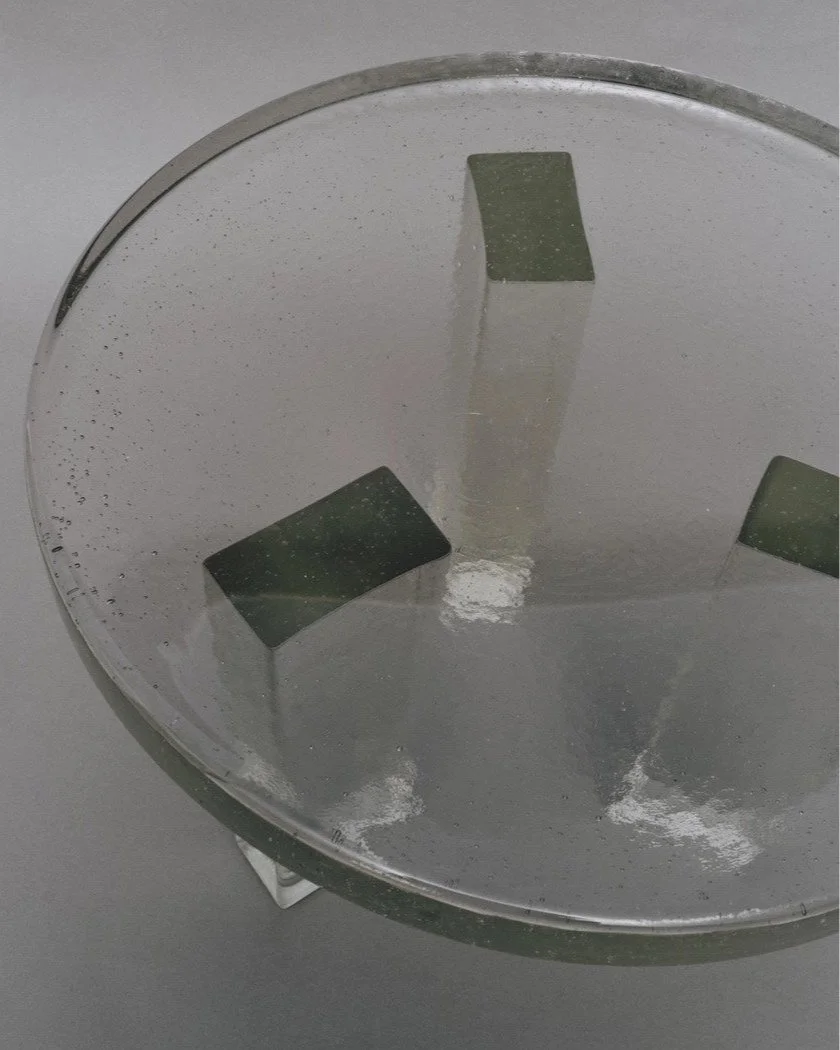

One might ask, therefore, which of those pieces by à la mode makers might at some point in the distant — or even very near — future become coveted by collectors; this doesn’t necessarily mean items that are cutting edge in terms of their inherent avant-garde credentials, but rather works that have a certain je ne sais quoi that sets them apart from the pack. Whilst there are numerous “big names”, such as Charles Zana, Eric Schmitt (b. 1955) and Pierre Yovanovitch (b. 1965), whose “Papa Bear” armchair and “Flare” floor lamp have become mainstays of contemporary, luxury interiors, there are also those lesser known designers whose refined sensibilities have captured the cognoscenti’s attention. Since its inception, The Row has championed decorative arts, displaying a panoply of discreetly desirable works throughout their carefully curated interiors; a feat made possible thanks to a bravura of art world sourcing partners, including such luminaries as Jacques Lacoste, Patrick Seguin, Galerie 54, Oscar Graf and Kayne Griffin. As such, for their first stand-alone boutique on Melrose Avenue, Los Angeles, company founders, Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen (b. 1986) turned to Los-Angeles based designer Courtney Applebaum, who, of her approach to interiors explains, matter of factly: “Houses should be a reflection of the people that live in them. People are not one-dimensional, in my opinion, [and] if you are, I probably don’t want to see your house!” Applebaum launched her debut furniture collection in 2022, and her monolithic, slab-like “Seeded Glass” tables are particularly wonderful; at once evocative of the thick Saint-Gobain tabletops beloved by French modernists such as Chareau and Jacques Adnet (1900-1984), but, at the same time, frameless, and employing only one material, they feel wholly fresh, unexpected and original. Used by a panoply of in demand designers such as Ashe Leandro and Francesco Paolini, they add a certain “edge” to those interiors composed by decorators with a penchant for twentieth-century design.

This is perhaps in some measure due to the elegant curation of Hollywood’s Seventh House Gallery, which, since staging exhibitions for Applebaum’s past two collections, has shown her work alongside an elegant amalgam of pieces by the likes of Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941), Gerald Summers (1889-1967) and Jean Després (1889-1980); creating an aesthetic that is, in essence, an expression of the Zeitgeist in terms of a newly minted generation of young collectors keen to snap up eye-catching, yet understated works of design that create a certain sense of depth and intrigue. Applebaum, as perhaps might be expected, is equally eloquent in discussing her approach, “The collections are aligned with the same design tenets as my interiors practice. Championing designs which underscore the inherent beauty in the balance held between eclecticism and measured restraint. Utilizing materials deeply tethered to the earth, each piece is uniquely grounded. The influences in the forms are inspired by silhouettes which have been revered and used as points of inspiration by designers spanning across design periods and styles.” In a similar way to American decorator Eyre de Lanux (1884-1996), Applebaum is drawn to rudimentary materials, such as terracotta and raffia, that offset the sort of streamlined art moderne silhouettes that influenced her collections; with each piece, in part as a result of the designer’s decidedly restrained palette, expressing a certain monolithic, minimal simplicity, an aesthetic that chimes with an increasing desire for “quiet luxury”, or rather, interiors that celebrate craftsmanship, quality and form over editorial fireworks. “As with interiors, my approach tends to be more intuitive and instinctual, but rooted in my love of the history of design,” Applebaum explains. “I don’t use many contemporary pieces and I love nothing more than the feeling of when I discover an antique or vintage piece that I find beautiful. It’s a romantic and joyous sensation, a state of wonderment. I get that same feeling working with these materials and figuring out, through research, new ways to form them.”

The “Otto” sofa by Paris-based interior architect Valériane Lazard for Ormond Editions, shown at last years PAD London, image c/o Ormond Editions

Apparatus Studio's monumental hand-embroidered “Interlude” hanging lamp, illuminating the sweeping Villa Necchi-esque staircase at their recently opened Mayfair showroom, image c/o Apparatus

Since the 2022 sale of Hubert de Givenchy’s (1927-2018) collection at Christie’s, and François Halard’s (b. 1981) atmospherically charged catalogue photographs, we were reminded of the couturier’s extraordinary ability to combine ancient regime and art moderne in a way that seemed fresh and modern; Rothko, Miró (1893-1983), Picasso (1881-1973) and the Giacometti brothers, Alberto and Diego (1902-1985), were juxtaposed in happy harmony against seventeenth-century Boulle cabinets, ormolu “objets d art”, silver bibelots and bronze sculptures. As such, there has been a renewed and revived interest in collecting antiques, and with it a fresh generation of dealers keen to recontextualize eighteenth-century fauteuils and Empire Gueridon for those interested in compiling a collection dating back further than 1925. In terms of contemporary design, that takes inspiration from the past, French interior decorator Léo Sentou (b. 1983) launched his first capsule collection last year, with pieces that appear unashamedly modern, yet found their form in what he refers to as the “extreme refinement” of eighteenth-century French furniture, and inherent modernity of makers such as Georges Jacob (1739 -1814) and Louis Delanois (1731-1792). For that reason, Sentou was recently appointed to “Le French Design 100” for his wrought iron and alabaster “Side Table L.A”, an elegant, pared-back reinterpretation of a “servante monopole” by master cabinetmaker Louis Aubry (1741-1814), that perfectly encapsulates the sort French savoir-faire that sets the “City of Light” apart from others apropos its pared-back approach to classicism. Similarly, his plush, mohair upholstered “L.D. Armchair”, with its “gauged bronze” feet is destined to become a true design classic, its gentle, undulating curves evocative of an elegant oval bergère, and at the same time, bringing to mind the Neoclassical works of Art Deco ébéniste’s Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann (1879-1933), Dominique and Paul Dupré-Lafon (1900-1971). In essence, by taking the same references, Sentou is developing a wholly original vocabulary, that feels at once of its era, and at the same time, evokes a Proustian association with the past; as could be seen to great effect during the exhibition “Savoir-Faire & Architecture” (2023) at Féau Boiseries during Paris Design Week, when the “L.D” was displayed against banks of Louis XVI panelling. “I feel I’m a contemporary classicist — if such a term can be employed — and find inspiration in both old and new,” explains Sentou. “When developing my collection, I wanted to respect the sort of simple, pure shapes that such makers as Georges Jacob and Jean-Baptiste Tilliard strove to achieve, but at the same time, I had no desire to rehash the past or play with nostalgia. I wanted to capture what I see as the essence of eighteenth-century furniture without being a prisoner to it.”

The plush, mohair upholstered “Fauteuil L.D”, by French designer Léo Sentou, seen here at the Invisible Collections Saint Germain showroom, image c/o The Invisible Collection

Courtney Applebaum’s monolithic, slab-like “Seeded Glass” table, evocative of thick Saint-Gobain tabletops beloved by French modernists such as Chareau and Jacques Adnet, image c/o Seventh House Gallery

The post-war years saw an explosion of designers such as Gabriella Crespi (1922-2017) and latterly, Guy de Rougemont (1935-2021) and Michel Boyer (1935-2011), who created cutting-edge furniture from brass, steel, and aluminium, beloved by designers such as Charles Sevigny (1918-2019), Isabelle Hebey (1935-1996) and François Catroux (1936-2020); in part, as they provided a contemporary counter to the sort of heavily ornamented apartments their clients more often than not inhabited. Crespi saw her career peak during the latter half of the twentieth century, creating a series of fantastical works such as her elliptical “Elisse” low table (c. 1970), “Z” writing desk (1974) and “Small Lune” collection, consisting of polished steel light sculptures inspired by the phases of the moon (something of a leitmotif in Crespi’s extensive oeuvre). Her sleek, futuristic aesthetic, smoothed by a profound sentiment for the cosmic power of nature, truly captured the spirit of an increasingly liberal and emancipated generation, embracing “newness” in all its forms. Similarly, Rougemont’s plexiglass and stainless steel “Nuage” coffee table, created in 1970 as part of a commission for design grandee Henri Samuel (1904-1966), is on the cusp between Pop Art and Minimalism. The artist had previously presented cloud-shaped sculptures at Galerie Suzy Langlois in 1969 that resonated with Samuel, and as a result of his unmatched influence, rather extraordinarily, he persuaded Rougemont to create cloud-shaped furniture. Giving it an especially ‘70s feel, preliminary models, rather wonderfully, were augmented with concealed lighting, lending, for those who so desired, a certain space-age Studio 54 vibe to any blue-chip collection of modern masters. The model has, since, become an icon of mid-century avant-garde design, gaining something of a cult following amongst a rarified group of collectors.

For an entirely new take on such hard-edged sculptural works, look no further than New York-based decorator and designer Brett Robinson (b. 1991), who creates extraordinary furniture from cast aluminium, including tables with reinforced epoxy tops as well as sofas and stools upholstered in plush alpaca, with undulating lines reminiscent of Mark Newson’s (b. 1963) groundbreaking “Orgone” collection, and the captivating way in which he was able to portray metal as if a soft and pliable material (interestingly, in a design world that’s nothing if not cyclical, despite the avant-garde appearance of Newson’s cutting edge designs, the curvaceous profile of his “Pod of Drawers” (1987) openly references French ensemblier Andre Groult’s (1884-1966) celebrated “Chiffonier Anthropomorphe” of 1925). Growing up in Manhattan Beach, California, Robinson found his way into the world of interiors as a result of his aversion to skateboarding, spending his teens scouring flea markets and in turn, developing a passion for vintage furniture. His first collection, titled “Halcyon”, was shown in Los Angeles at Just One Eye — tastemaker Paula Russo’s much-lauded “future concept store” — alongside a typically eclectic curation of Art Deco furniture, Jacques Grange tableware and photographs by Andy Warhol (1928-1987), Nobuyoshi Araki (b. 1940) and Thomas Ruff (b. 1958). Yet even amongst such art world heavyweights, the sheer quality and originality of Robinson’s work sings out; with the strength of its sculptural presence reminiscent of Isamu Noguchi’s (1904-1988) much imitated mid-twentieth century creations. On that note, when asked to proffer an opinion as to why the market for decorative arts is seeing an explosion of interest among Gen Z and Millenial collectors, Robinson replies simply, “Tastes change, but good design doesn’t”, and who can disagree with that?

In terms of truly original works, Ian Felton’s (b. 1992) “Sacha” coffee table, named after the Quechua word for “Tree” — first exhibited at the “Instafamous” home-cum-work space of multi-hyphenate gallerist and interior designer Michael Bargo — has a similarly sculptural aesthetic, with its root-like, rough-hewn oak base and glazed lava stone top, evocative of submerged coral. The designer has in the past spoken of the difficulty of being an active participant in the industry, while at the same time maintaining a unique viewpoint, extraneous to fads and fast fashions. Of the inherent paradox he laments, so as to remain uninfluenced, “I siphon myself off from the rest of the design world as much as possible”. It might then perhaps come as little surprise that some of Felton’s influences seem a little out of left field. While in the throes of research, the designer stumbled across Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley’s “Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design” (2016), something of a polemical book rethinking the philosophy of design from antique tools and ornaments to the buzz of the digital era. Felton subsequently found himself drawn to Pre-Columbian cultures and the way in which, regardless of whether it was “a flute or a spoon or a vessel”, they imbued objects with a sense of storytelling and animism. That being so, he has no interest in mimicking their specific design details, as is immediately apparent, but rather, seeks to convey a similar energy, whereby the resultant works can be seen as an homage. Felton’s oeuvre is somewhat unique in the way it intertwines industrial design, furniture design and design for sustainability, creating cultural objects inspired by nascent societies that counter what American decorator Paul Fortune (1950-2020) dubbed “Nightmare-on-West-Elm-Street disease”, or rather, the editorially driven trend for homogenous interiors; a phenomenon increasingly dictated by a cabal of “celebrity” stylists hell-bent on accessorising every interior with the same ton sur ton amalgam of Axel Vervoordt-esque objets d’art.

As can be seen in the work of Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941) and Atelier Martine, furniture needn’t necessarily scream and shout so as to become sought after and desirable, and for more pared-back pieces, one might look to Garnier et Linker, whose beautifully crafted works speak of understated, refined luxury, as seen in their recent collaboration with Galerie Dutko, a contemporary take on the work of Eugène Printz (1889-1948), who, of course, gallery founder Jean-Jacques Dutko quite literally wrote the book on. Paris-based interior architect Valériane Lazard is another whose work expresses a certain subtle eloquence and timelessness that appeals to collectors. On that note, for something that has a presence in and of itself, akin to the work of Carlo Bugatti (1856-1940) or Armand-Albert Rateau (1882-1938), Gabriel Hendifar of Apparatus Studio creates furniture and lighting truly spectacular in its conception, with a certain luxurious masculinity and richness of materials evocative of the cinematic glamour of 1930s Milanese rationalism. This is an aesthetic evinced to full effect in the walnut-panelled interiors of their recently opened Mayfair showroom; where a monumental hand-embroidered “Interlude” hanging lamp illuminates the sweeping Villa Necchi-inspired staircase. While some lament contemporary design, sniffily suggesting it’s somehow inferior to, or merely derivative of past, “superior” ébénistes, it’s clear that there are, thankfully, a pocket of talented contemporary designers producing works as captivating as their forbears, that will, one day, become as collectable as that of Jean Royère (1902-1981), Mathieu Matégot (1910-2001) or Jean-Baptiste-Claude Sené (1748-1803). As such, we should encourage creativity in all its forms, celebrating true talent and originality as opposed to those who spin a good yarn, with no real substance, or, to coin a phrase, the “editorially fashionable”.